Picture this: you’re helping a friend move into their new apartment, and you’re stuck in a narrow L-shaped hallway with their massive sectional sofa. No matter how you twist, turn, or angle it, the thing just won’t fit around that corner. You’re sweating, your back aches, and you’re wondering if you’ll have to take the whole thing apart.

What you don’t realize is that you’re wrestling with one of mathematics’ most stubborn puzzles. For nearly 60 years, brilliant minds have been trying to solve the exact same problem you’re facing, except they call it the “moving sofa problem.”

That frustrating moment just became a lot more interesting, because a 31-year-old mathematician from South Korea has finally cracked this legendary puzzle that stumped generations of researchers.

When Moving Day Becomes Mathematical History

The moving sofa problem sounds deceptively simple. Back in 1966, mathematician Leo Moser posed a question that any homeowner would recognize: what’s the largest rigid flat shape you can maneuver around an L-shaped corner in a hallway that’s exactly one meter wide?

Think about it for a moment. A simple rectangle won’t work well because it gets stuck at the corner. A circle is better, but it wastes space. So what’s the perfect shape that maximizes area while still making that crucial turn?

This innocent-sounding puzzle quickly became legendary in mathematical circles. Despite decades of attempts, computer simulations, and brilliant theoretical work, nobody could definitively solve it. Until now.

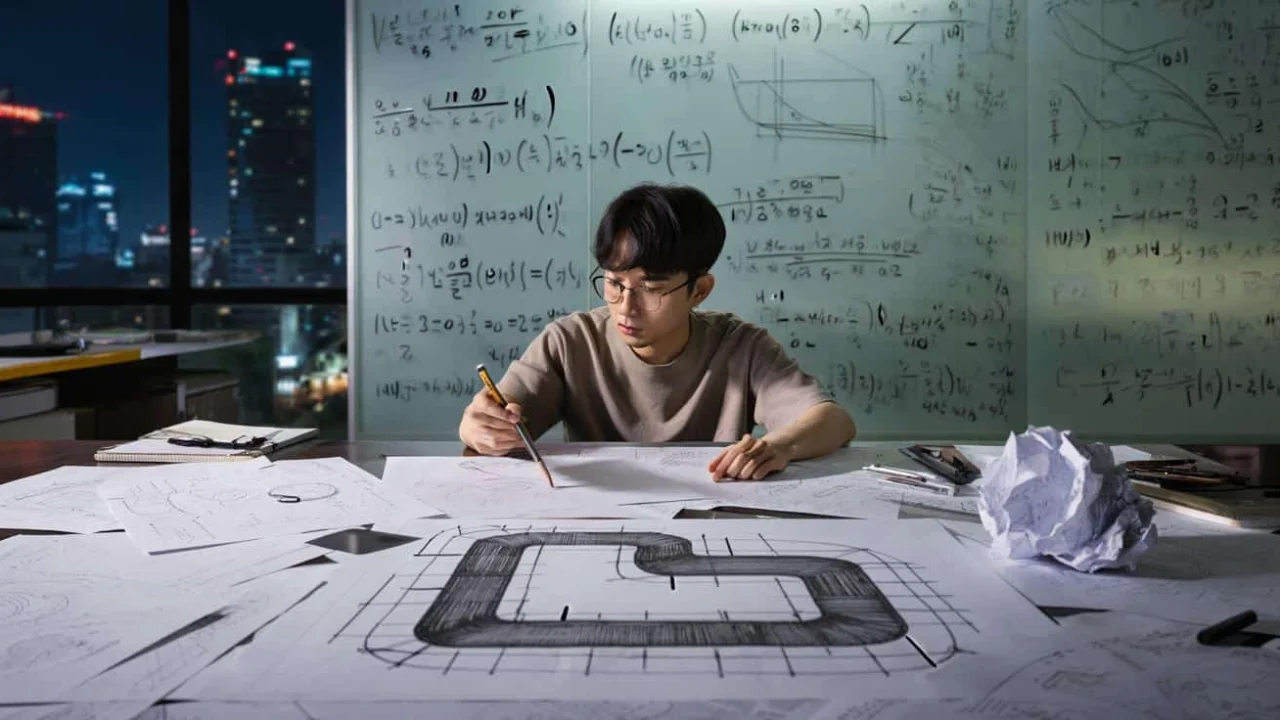

Baek Jin-eon, a young mathematician doing his mandatory military service at South Korea’s National Institute for Mathematical Sciences, has accomplished what seemed impossible. Using nothing but pencil, paper, and extraordinary patience, he’s provided the mathematical proof that finally closes this 60-year-old question.

The Journey from Student Dorms to Mathematical Glory

The moving sofa problem has a fascinating history of near-misses and incremental progress. Here’s how mathematicians have tackled this challenge over the decades:

- 1968: John Hammersley designed a shape with an area of about 2.2074 square meters

- 1992: Joseph Gerver created a complex, curved design reaching 2.2195 square meters

- 2018: Various computer simulations suggested Gerver’s shape might be optimal

- 2024: Baek Jin-eon provides the mathematical proof

“What made this problem so difficult wasn’t finding better shapes, but proving that no better shape could exist,” explains Dr. Sarah Mitchell, a geometry professor at Cambridge University. “Baek’s work finally provides that mathematical certainty.”

| Year | Mathematician | Shape Area (m²) | Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | John Hammersley | 2.2074 | First major improvement over basic shapes |

| 1992 | Joseph Gerver | 2.2195 | Complex curved design, long-standing record |

| 2024 | Baek Jin-eon | 2.2195 | Mathematical proof of optimality |

Gerver’s shape looked bizarre—imagine a sofa designed by someone having a fever dream. It featured multiple curves, strategic indentations, and careful angles that somehow managed to squeeze through that L-shaped turn while maximizing area.

For over 30 years, mathematicians suspected Gerver’s design was optimal, but they couldn’t prove it. Computer simulations supported this hunch, but simulations can only test specific shapes and approximations. They can’t provide the mathematical certainty that no better solution exists.

Why This Mathematical Breakthrough Matters Beyond Moving Day

You might wonder why anyone cares about the optimal sofa shape. After all, real sofas come in standard sizes, and most people just hire professional movers when things get tricky.

But the moving sofa problem represents something much bigger in mathematics and engineering. It’s part of a field called geometric optimization, which has real-world applications that touch our daily lives in surprising ways.

Consider these practical applications:

- Robotics: Autonomous vehicles need to navigate tight spaces and complex turns

- Manufacturing: Factories must optimize how parts move through assembly lines

- Architecture: Buildings need efficient layouts for moving equipment and materials

- Emergency Services: Ambulances and fire trucks must navigate narrow urban streets

“This isn’t just about furniture,” notes Dr. James Chen, a robotics engineer at MIT. “The mathematical principles behind Baek’s proof could influence how we design everything from warehouse robots to surgical instruments.”

The breakthrough also demonstrates the power of pure mathematical thinking. While others relied on computer simulations and approximations, Baek used traditional mathematical proof techniques to achieve absolute certainty.

His approach involved advanced calculus of variations and optimal control theory—mathematical tools that sound intimidating but essentially help find the best possible solution to complex optimization problems.

From Military Service to Mathematical Stardom

Baek’s discovery during his military service adds an interesting human element to this mathematical triumph. South Korea requires most young men to complete military service, often interrupting their academic or professional careers.

Instead of seeing this as a setback, Baek used his placement at the National Institute for Mathematical Sciences as an opportunity to tackle one of mathematics’ most famous unsolved problems.

“Sometimes the best insights come when you approach a problem with fresh eyes and no preconceptions,” observes Professor Lisa Wang, a mathematician at Seoul National University. “Baek didn’t carry the baggage of decades of failed attempts.”

The mathematical community has responded with enthusiasm and some amazement. Solving a problem that stumped researchers for 60 years is impressive enough, but doing it with traditional paper-and-pencil methods in an era dominated by computational approaches makes it even more remarkable.

Baek’s proof runs over 100 pages and involves sophisticated mathematical techniques, but its core insight is elegantly simple: he found a way to prove that any shape larger than Gerver’s design would inevitably get stuck at some point during the turn.

This breakthrough joins a select group of recently solved mathematical puzzles that captured public imagination, including the Poincaré Conjecture and Fermat’s Last Theorem. Each solution required years of dedicated work and novel mathematical insights.

FAQs

What exactly is the moving sofa problem?

It’s a geometry puzzle asking for the largest rigid flat shape that can be moved around an L-shaped corner in a hallway that’s one meter wide.

How long has this problem been unsolved?

The moving sofa problem was first posed in 1966 by Leo Moser, making it nearly 60 years old when Baek Jin-eon solved it.

What makes this solution special compared to previous attempts?

Baek provided a complete mathematical proof that Gerver’s 1992 design is optimal, meaning no larger shape can possibly work.

Does this have any practical applications?

Yes, the mathematical principles apply to robotics, manufacturing, architecture, and any field requiring optimization of movement through constrained spaces.

Why couldn’t computers solve this problem earlier?

Computers can test specific shapes but can’t prove that no better shape exists. That requires the kind of rigorous mathematical proof that Baek provided.

What’s next for Baek Jin-eon?

Having solved one of mathematics’ famous problems, he’s likely to receive significant academic opportunities and recognition in the mathematical community.