Sarah never forgot the day her oncologist delivered the news with a gentle but firm voice: “The immunotherapy isn’t working.” After months of hope, watching other patients respond beautifully to checkpoint inhibitors, her breast cancer remained stubbornly invisible to her own immune system. It was like her T cells were looking right through the tumor, treating it as if it belonged there.

For Sarah and millions like her, cancer had found the perfect hiding spot—right in plain sight. But now, researchers in China believe they’ve discovered a way to tear away that cloak of invisibility, using an unexpected ally: the memory of old viral infections we all carry.

This breakthrough represents a fundamental shift in cancer immunotherapy, one that could finally reach the patients who’ve been left behind by current treatments.

When Your Immune System Can’t See the Enemy

Modern cancer immunotherapy has achieved remarkable victories. Checkpoint inhibitor drugs like anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies work by releasing the brakes on T cells, essentially giving your immune system permission to attack tumors it previously ignored.

But here’s the frustrating reality: roughly 60-70% of cancer patients see little to no benefit from these treatments. The reason isn’t that the drugs don’t work—it’s that some cancers are masters of disguise.

“These tumors carry very few mutations, so they don’t generate enough warning signals for the immune system to recognize them as threats,” explains Dr. Jennifer Wang, an immunologist not involved in the study. “It’s like trying to spot a criminal who looks exactly like everyone else in the crowd.”

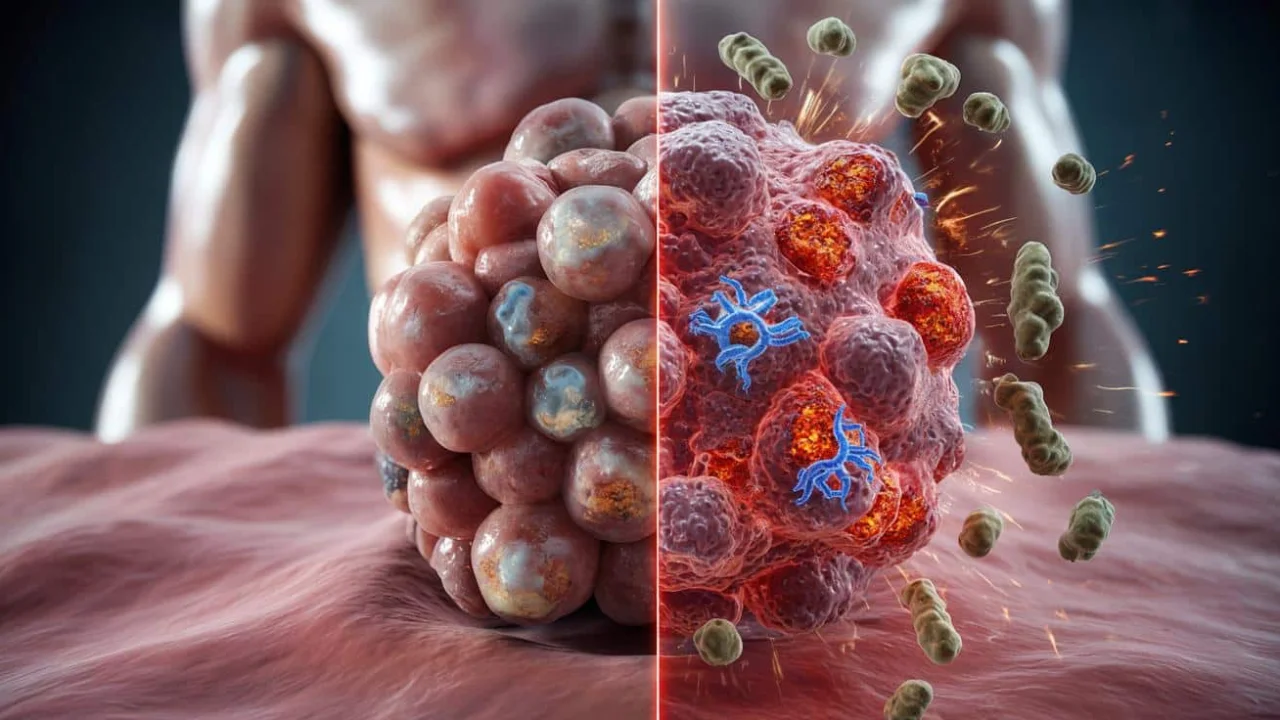

These so-called “cold” tumors have another trick up their sleeve. They often produce excessive amounts of PD-L1, a protein that actively shuts down nearby T cells. Even when patients receive checkpoint inhibitors, there simply aren’t enough recognizable targets on the cancer cells to spark a meaningful immune response.

The Revolutionary iVAC Strategy

Researchers from Shenzhen Bay Laboratory and Peking University approached this problem from an entirely new angle. Instead of hunting for rare tumor-specific markers, they asked a brilliant question: What if we could redirect the body’s existing army of memory T cells toward cancer?

Think about it—most adults carry powerful, long-lived T cells that remember past battles with common viruses like cytomegalovirus (CMV) or the chickenpox virus. These cellular warriors are numerous, highly trained, and ready to respond at a moment’s notice.

The team developed a synthetic creation called iVAC (intratumoral vaccination chimera) that performs two coordinated functions:

- Strips away PD-L1 proteins that suppress immune responses

- Forces cancer cells to display viral fragments on their surface

- Activates memory T cells that recognize these viral signatures

- Converts “cold” tumors into “hot” targets for immune attack

| Traditional Approach | iVAC Strategy |

|---|---|

| Relies on tumor-specific mutations | Uses viral memory T cells |

| Limited targets available | Abundant memory cells ready |

| Works in 30-40% of patients | Potentially effective in more cases |

| Depends on natural tumor antigens | Creates artificial viral targets |

“We’re essentially playing a trick on the immune system,” says lead researcher Dr. Chen Liu. “We’re making cancer cells wear the costume of an old viral enemy that the body already knows how to fight.”

How This Could Change Everything

The implications of this research extend far beyond the laboratory. For patients like Sarah, whose tumors have been invisible to conventional immunotherapy, this approach offers genuine hope.

The beauty of the iVAC system lies in its simplicity and universality. Since most adults have been exposed to common viruses throughout their lives, nearly everyone carries the necessary memory T cells that this therapy would activate.

Early laboratory results show that tumors treated with iVAC become significantly more visible and vulnerable to immune attack. The synthetic chimera essentially rewires the tumor’s identity, transforming it from an ignored bystander into a high-priority target.

“What excites me most is that this approach doesn’t require finding unique mutations in each patient’s tumor,” notes Dr. Michael Rodriguez, an oncologist at a major cancer center. “It taps into the immune memory we all share from common infections.”

The treatment is designed to be injected directly into tumors, allowing for precise targeting while minimizing systemic side effects. This local delivery method could make the therapy safer and more tolerable than traditional approaches.

Real-World Impact for Patients

If clinical trials prove successful, this technology could dramatically expand the reach of cancer immunotherapy. Patients with traditionally resistant cancers—including certain types of breast, pancreatic, and brain tumors—might finally have access to effective immune-based treatments.

The financial implications are equally significant. Rather than developing entirely new drugs for each cancer type, this approach could potentially work across multiple tumor types by leveraging the same viral memory pathways.

“We’re looking at a potential paradigm shift,” explains Dr. Sarah Chen, who specializes in cancer immunology. “Instead of chasing after elusive tumor antigens, we’re recruiting an army that’s already trained and ready for battle.”

However, researchers caution that significant hurdles remain. The technology must prove safe and effective in human trials, which could take several years to complete.

The next phase involves testing iVAC in animal models before moving to human clinical trials. Researchers are particularly interested in combination approaches, where iVAC might be used alongside existing checkpoint inhibitors for enhanced effectiveness.

For now, patients and families affected by immune-resistant cancers can take hope in knowing that brilliant minds are working on creative solutions to one of medicine’s most challenging puzzles. The idea that our body’s memory of past infections could become a weapon against cancer represents the kind of innovative thinking that drives medical breakthroughs.

FAQs

How does iVAC make cancer cells visible to the immune system?

iVAC forces cancer cells to display viral fragments on their surface that memory T cells from past infections can recognize and attack.

Is this treatment available to patients now?

No, iVAC is still in early research phases and needs to complete clinical trials before becoming available to patients.

Would this work for all types of cancer?

Researchers believe it could work across multiple cancer types, but more testing is needed to determine its full range of effectiveness.

Are there side effects from using viral memories?

Since the treatment uses the body’s natural immune memory, researchers expect fewer side effects, but clinical trials will determine safety.

How long until this might reach patients?

If trials go well, it could take 5-10 years before this treatment becomes widely available to cancer patients.

Could this replace current immunotherapy drugs?

Rather than replacing them, iVAC might work best in combination with existing checkpoint inhibitors for enhanced effectiveness.