Marie Novakova remembers the blackouts of 1989, when Czechoslovakia’s aging power grid couldn’t keep up with demand. Now 58 and living in Prague, she watches the news about her country’s nuclear future with the same anxiety she felt back then. “We need reliable electricity,” she tells her neighbors over coffee. “But this fight over billions of euros… it makes me nervous.”

Marie’s concerns reflect what millions across Central Europe are feeling right now. The Czech nuclear contract worth €16.4 billion has become more than just a business deal—it’s a symbol of energy independence, economic sovereignty, and the complex web of European politics.

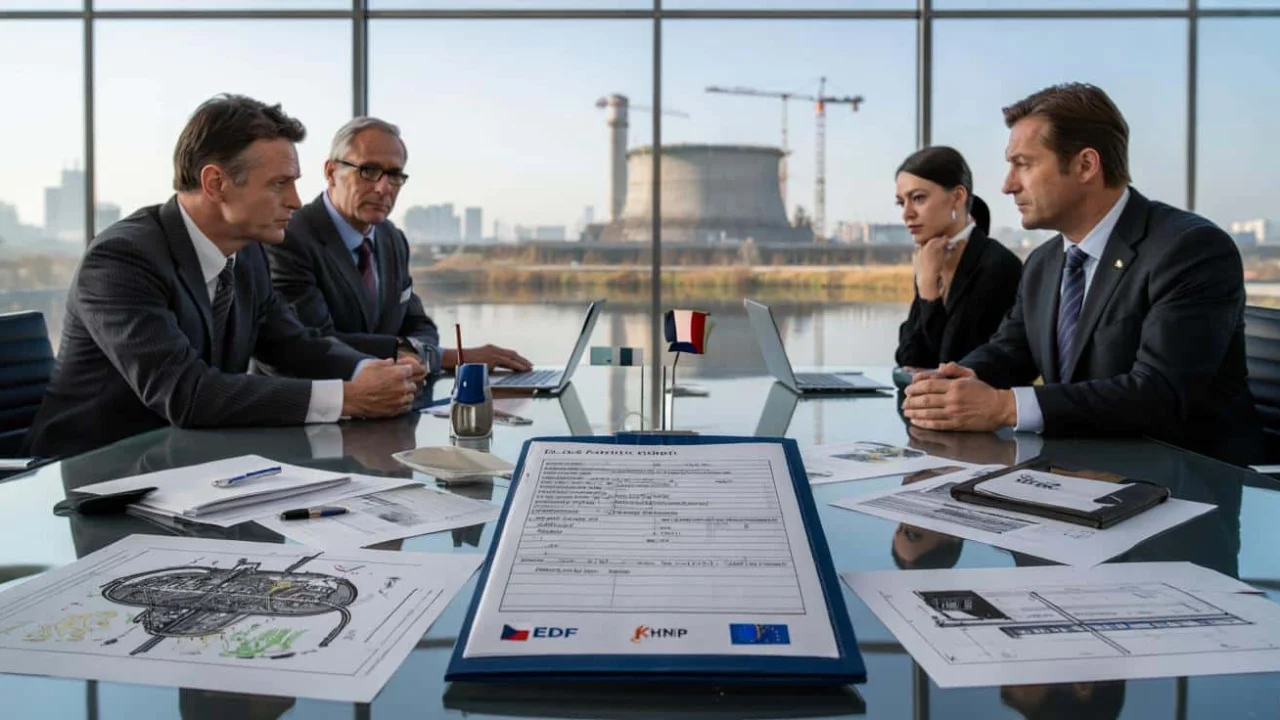

What started as a straightforward infrastructure project has exploded into a three-way battle between Prague, Brussels, and competing nuclear giants. And surprisingly, French utility EDF isn’t out of the game yet.

Why This Contract Became Europe’s Biggest Energy Fight

The Czech Republic doesn’t mess around when it comes to nuclear power. About one-third of the country’s electricity already comes from atomic reactors, and officials want to keep it that way for decades to come.

The problem? The four reactors at Dukovany are getting old. Built in the 1980s during Soviet times, they’re still running but won’t last forever. Czech leaders see new reactors at the same site as absolutely critical for their energy future.

In 2024, Prague made what seemed like a final decision: they picked Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) over EDF to build two massive new reactors. KHNP’s bid came in at roughly €8.2 billion per reactor, promising tight schedules and cost control.

“The Koreans offered exactly what we needed—proven technology with realistic timelines,” explained a Czech energy ministry official familiar with the negotiations.

But here’s where things got complicated. The Czech government didn’t just want to buy reactors—they designed an incredibly generous financing package that would essentially eliminate financial risk for the chosen contractor.

The Money Trail That Caught Brussels’ Attention

The financing structure Prague created is unlike almost anything Europe has seen before. It’s so generous that European Commission officials started asking serious questions about whether it violates EU state aid rules.

Here’s how the Czech plan works:

- A state-backed loan covering 100% of construction costs

- A 40-year price guarantee for all electricity produced

- Legal protection against policy changes

- Government ownership of most financial risk

The total public money involved is staggering. While the pure construction cost is around €16.4 billion for both reactors, Brussels estimates the complete financial commitment could reach €23-30 billion once interest, fees, and risk buffers are included.

| Component | Value (Billions €) | Risk Holder |

|---|---|---|

| Base Construction Cost | 16.4 | Czech State |

| Interest & Fees (est.) | 6-10 | Czech State |

| Risk Buffers | 1-4 | Czech State |

| Total Exposure | 23-30 | Czech State |

“This isn’t just state aid—it’s state aid on steroids,” commented a European energy analyst who requested anonymity. “The Czech government is essentially acting like an insurance company for the entire project.”

Under the Contract for Difference mechanism, Prague guarantees a fixed price per megawatt-hour for 40 years. If market prices fall below that level, taxpayers make up the difference. If prices rise above it, the plant pays money back to the state.

How EDF Got a Second Chance

This is where the story takes an unexpected turn. The European Commission launched a formal investigation into whether the Czech nuclear contract violates EU competition law. If Brussels rules that the financing package constitutes illegal state aid, the entire deal could be overturned.

That would put EDF right back in the running for what industry insiders call “the contract of the century.”

EDF’s original bid was reportedly higher than KHNP’s, but the French company has argued that their technology and experience justify the premium. They’ve also suggested they could work within modified financing terms that might satisfy EU regulators.

“We remain ready to deliver world-class nuclear technology to our Czech partners,” an EDF spokesperson said recently. “Our EPR reactors represent proven European technology with strong safety records.”

The timing couldn’t be better for EDF’s hopes. The company has been struggling with cost overruns and delays on other projects, making the Czech nuclear contract a potential lifeline for their international expansion plans.

What This Means for Energy Bills and Independence

For ordinary Czech citizens like Marie, this political drama has real consequences. Nuclear power represents one of the few ways small European countries can achieve genuine energy independence.

The war in Ukraine drove home how dangerous it can be to rely on energy imports from unstable regions. Nuclear reactors, once built, can run for 60-80 years with fuel that’s relatively easy to source and store.

But the financial model Prague chose also means taxpayers are on the hook if things go wrong. Nuclear projects have a history of massive cost overruns—just look at the troubled construction of new reactors in Finland, France, and the UK.

Here’s what different outcomes could mean:

- If KHNP proceeds: Czech energy independence with Korean technology, but potential EU legal challenges

- If EDF wins on appeal: European technology keeping jobs in the EU, but possibly higher costs

- If the project collapses: Continued reliance on aging reactors and energy imports

“We’re walking a tightrope between energy security and financial responsibility,” admitted a Czech parliamentarian involved in energy policy discussions.

The broader implications extend beyond Czech borders. Other Central European countries are watching closely, as they face similar decisions about replacing Soviet-era nuclear plants. Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania all have major nuclear investment plans that could be affected by the precedent set in Prague.

Whatever happens with the Czech nuclear contract will likely influence how future energy infrastructure projects are financed across Europe. Brussels is clearly drawing red lines around how much state support governments can provide to private companies, even for strategically important projects.

For now, Marie and millions of other Europeans can only wait and see whether their leaders can balance the competing demands of energy security, fiscal responsibility, and EU law. The outcome will shape the continent’s energy landscape for generations to come.

FAQs

What is the Czech nuclear contract worth?

The base construction cost is €16.4 billion for two reactors, but total government financial exposure could reach €30 billion including financing costs.

Why is the European Commission investigating?

Brussels is concerned that the extremely generous financing terms constitute illegal state aid that violates EU competition law.

Can EDF still win the contract?

Yes, if the European Commission overturns KHNP’s victory due to state aid violations, EDF could get another chance to bid.

When will the new reactors be built?

If the project proceeds, construction would begin around 2029-2030, with the first reactor potentially online by the late 2030s.

Why does this matter for energy security?

Nuclear power provides baseload electricity without fossil fuel imports, helping countries achieve energy independence from potentially unstable suppliers.

What happens to Czech energy if the project fails?

The country would need to extend the life of aging Soviet-era reactors or increase reliance on energy imports, both risky long-term strategies.